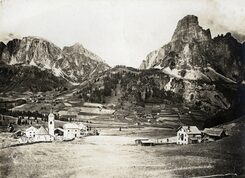

The Dolomites, also known as the “Pale Mountains”, are a mountain range in the northern Italian Alps covering an area that is shared by the provinces of Belluno, Bolzano, Trento, Udine, and Pordenone.

Their geographic extension, however, is not simply based on complex and unusual geological elements; it also finds its roots in tradition and in the pages of history, which more or less coincide with the widespread idea of the Dolomites that people have today. The Dolomite region is characterized by jagged peaks and ridges with scenic valleys nestled in between.

Its inhabitants speak different languages: German is spoken in the north and northwest; Italian in the south; and Ladin in the central area – in the four valleys that branch off the Sella Massif (Val di Fassa, Val Gardena, Val Badia, and Livinallongo) – and in Ampezzo. The most renowned tourist locations in the Dolomites can be easily reached from the nearest airports of Venice or Innsbruck – roughly a 2.5 hr drive.

For many years, the Pale Mountains in the South Tyrol and in the Veneto Region that today comprise the UNESCO World Heritage Site remained unexplored by outsiders. Only a few inhabitants of the valleys carved out within the mountains had some knowledge of their environs. Up until the 18th century, the range didn’t even have a name. The name “Dolomites” is in fact relatively new. This is probably why the local population today still uses the names of individual peaks that they have walked or climbed up instead of using the name “Dolomites”.

Igor Tavella, a known sportsman and hotel entrepreneur in Badia, remembers:

“When we were young, we went to school in San Leonardo and a little way up we could see the majestic Sasso della Croce with the peaks Cima Nove and Cima Dieci to the left and the peaks of Lavarella and Conturines to the right. On the other side of the town is the Gardenaccia plateau and, if you look towards Corvara, you can see the Sassongher. To learn the four cardinal directions, we were taught at school to look at how the sun moved through these mountains – from dawn to dusk and according to the seasons. For example, if the sun rises behind the Conturines massif in January, as spring nears you can see the sunrise behind the Lavarella, on the peak of Val Medesc, above the “Ciaval” – that’s the Ladin name for Sasso della Croce’s main peak – until it finally rises behind Cima Nove (Peak Nine). That’s where the sun is at 9 in the morning on the day of the Summer Solstice if you look at the sun from the village of La Valle. That’s how the peak got its name. In the same vein, the sun sets behind the Gardenaccia plateau in winter and sets behind the Putia in summer.”

A mineral and a place-name

The name “Dolomites” acknowledged worldwide today is actually recent. To learn how and when the Pale Mountains were named “The Dolomites,” we need to go back more than two centuries ago when the French geologist Marquis Déodat Guy Silvain Tancrède Gratet de Dolomieu (1750-1801) – on one of his field trips in the South Tyrol between 1789 and 1790 – observed that, “Certain rocks found along the road between Trento and Bolzano that are whitish in color and full of cavities containing rhomboid crystals do not effervesce in weak acid.” De Dolomieu was an extravagant and adventurous scientist who was greatly interested in mineralogy and vulcanology. He was fully aware that common limestone consists chiefly of calcium carbonate (CaCO3) and, therefore, is very effervescent when treated with hydrochloric acid. He took his samples to be analyzed by his friend Nicolas Théodore de Saussure, a chemist from Geneva and son of Horace Bénédict de Saussure, a prominent scientist, and alpinist who organized the first ascent on Mont Blanc in 1796.

N. T. de Saussure determined that the “slightly effervescent limestone” was not composed of common calcium carbonate (CaCO³) or magnesium carbonate (MgCO³), but rather was a double carbonate-containing calcium and magnesium with the chemical formula CaMg(CO³)². The spectacular pale mountains of the South Tyrol were therefore composed of a mineral that was until then without a known chemical formula. Initially, Dolomieu wanted to call it “saussurite”, but at a scientific meeting in 1796, Saussure proposed naming the new mineral “dolomite” in honor of who had discovered it.

Dolomieu was actually not the first to describe dolomite. It had previously been termed as “stinking spar”, “rhomboid spar”, “magnesian spar”, “muricalcite” and “magnesian carbonate”, but the new name of “dolomite” gained immediate success and supplanted any previous names.

Even so, no one had thought of extending the name of a mineral known by a few specialists to an entire region until the mid-1800s. This occurred when the first English mountaineers and travelers “discovered” the enchanted world of the Pale Mountains: in 1864, the painter Josiah Gilbert and the naturalist George C. Churchill published a book in London entitled “The Dolomite Mountains”, detailing their field trips in the Tyrol, Carinthia, Carnia, and Friuli took in 1861, 1862 and 1863, which ended with the chapter “Physical description of the Dolomite districts”. The designation of the Dolomites as an entire region was not, however, easily accepted. In 1879, the geologist Edmund Mojsisovics criticized the widespread use of naming an entire region based on a mineral because, as he rightly observed, dolomite mountains also exist in many other regions. Up until the early 1900s, very few publications explicitly cite the Dolomites; most scholars referred to the area as “Südtirol und Venetien”. It was only after the First World War that the terms Dolomites and Dolomite region became imbedded in common speech.

Children at school today learn that the wonderful mountains surrounding them since birth are the Dolomites. The word suits them because the first half of the word – “Dolo” – is “harmonious, almost as round as the landscape that frames the Dolomite Mountains, while the second half – ‘miti’ (“myths”, in Italian) – allow them to dream of the highest peaks and summits.” If we think of who discovered the dolomite rock – Déodat Guy Silvain Tancrède Gratet de Dolomieu, we feel we’re lucky to just have to remember the last part of his name! The real fortune, however, is perhaps being able to live in a paradise that is universally known: the Dolomites!

Click here to go to the next page 'Mountaineering and sport'