”A young Alpine mountaineer climbs the Dolomite peaks. He admires them, loves them, and feels his heart leap with joy as the subtle natural beauty of the mountain heights lies before him. He instinctively feels he should capture the moment. He’s able to do this with the modern – albeit rudimentary – photographic equipment available at the end of the 1800s, even though it is an arduous effort to carry his portrait cameras, dry plates, and tripods up to such altitudes, sometimes involving ascents onto rock walls.” (Theodor Wundt, Wanderungen in den Ampezzaner Dolomiten, 1895)

His hard work is rewarding: the pictures taken more than a century ago by the pioneers of mountaineering in the Dolomites evoke admiration and profound feelings even today. At the time, the magnificent works by German and English photographers that made the Dolomites known to mountain enthusiasts at the end of the 1800s – an important time in mountaineering – greatly encouraged travel to in the areas and valleys, from the sublime basin of Ampezzo that already welcomed thousands of tourists per year, to the Sella valleys: Fassa, Val Gardena, Val Badia, and Livinallongo.

Although many famous adventurers are included in the first pioneering phase in the Dolomites, historiographers usually attribute the leadership of “inaugurating the Dolomite era” to Vienna outdoorsman Paul Grohmann (1838-1908) because of his feats and, particularly, his writings. Grohmann was a founding member of the Austrian Alpine Club Österreichischer Alpenverein and reached Cortina in 1862. He was stunned to learn that nobody had ever climbed the magnificent peaks around the village. In the years to follow, Grohmann reached the summits of several peaks with the help of Francesco Lacedelli – nicknamed “Checo da Meleres”, who at age 60 became the first Alpine Guide in Ampezzo – and Angelo Dimai. He conquered Piz Boè in the summer of 1864 with Giuseppe Irschara, only to find signs left behind previously by a shepherd or a hunter. The same year, on September 28, Grohmann was the first to ascend the peak of Punta Penia (3,343 m a.s.l.) on the Marmolada together with Ampezzo guides Angelo and Fulgenzio Dimai. He was also the first to reach the summit of Sassolungo on 13 August 1869 with Peter Salcher and Franz Innerkofler. Following this feat, the same year Grohman was the first to climb the Cima Grande (“big peak”) of the Tre Cime di Laveredo with the guide from Sesto Pusteria, Franz Innerkofler.

In 1875 Grohmann significantly contributed to bringing the Dolomites to fame by publishing a detailed color map – the first of its kind – entitled “Karte der Dolomiten-Alpen”. Two years later he collected the most important aspects of his numerous ascents in the Dolomites in a travel book; “Wanderungen in den Dolomiten” (1877) was published in Vienna and covered Grohmann’s experiences between 1862 and 1869. The publication was an enormous success in all of Europe and stimulated mountain tourism in the Dolomite Ladin Valleys considerably, in particular to Cortina d’Ampezzo.

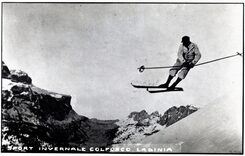

The first stage of pioneering ended when there were no more major first-ascents left to conquer. Mountaineers then began to search for new adventures on increasingly difficult rock walls, through single climbs, and winter ascents, sometimes with skis.

In the last two decades of the 19th century and in the early 20th century, enthusiasm for alpine mountaineering adventures still ran high. To capture this eagerness, mountaineering turned its attention towards first-ascents up minor peaks, many of which were in the Dolomites, and towards finding new routes to summits that had already been conquered. It was during this search for a new adventure that new climbing styles were developed: guideless climbing (climbing without an expert mountain guide), single climbing (without a rope team), winter mountaineering (involving the different and very challenging problems that snow and ice-covered mountains, extreme temperatures, and potential avalanches can pose), and ski touring (covering long distances in the “backcountry” on skis). These were the years of impressive personal achievements, such as the first winter ascents to Lavaredo’s Cima Piccola (“small peak”) and the Tofana di Mezzo in 1893 by the German climber Theodor Wundt, and feats by other great alpine mountaineers such as the Austrian Paul Preuss, the German Hans Dülfer, Tita Piaz from Val di Fassa – nicknamed “the devil of the Dolomites” for the audacity of many of his exploits – and Angelo Dibona from Ampezzo. Considering the rudimentary equipment available at the time, these mountaineers achieved an extremely high level of knowledge and skills – facing primarily Grade V difficulties. Most of the routes conquered during this period satisfy today’s numerous alpine mountaineers because their overall difficulty is no longer as extreme and their beauty is exceptional.

During the thirty years preceding World War I, a new force began to slowly and consistently energize the lives of the people living in the valleys in the entire Dolomite region. The local population began to see alpine tourism as an important opportunity to boost their otherwise precarious and extremely harsh economical and financial situation, and as a beacon for social change. The continuous and growing success of tourism in the Dolomites was favored by the construction of the Brennero and Val Pusteria railways and led to improvements in the existing – albeit few and extremely modest – local hotels. Many inns were transformed into comfortable hotels; homes became inns, and modest restaurants opened. The mountaineering clubs, especially the Austrian and German Alpine Club“Deutscher und Österreichischer Alpenverein” (D.u.Ö.A.V.), and the Italian Alpine Club together with the important “Società Alpinisti Tridentini” (S.A.T.) competed to build numerous shelters for mountaineers, even on some of the Dolomites’ most remote peaks.

Following the Great War, mountaineering turned towards conquering the Grade VI “heroic” challenges. Possibly the most emblematic climb of this historical period was the first ascent in 1933 by Emilio Comici of Trieste and Giuseppe and Angelo Dimai from Ampezzo, up the sheer, overhanging north face of the Cima Grande of the Tre Cime di Lavaredo – until then considered to be inaccessible. News of the event echoed worldwide and is today a classic climb for experts, seducing numerous experienced mountaineers.

The 1930s were some of Italian alpine mountaineering’s best years, perhaps due to heated feelings of revenge towards the German-speaking population and growing national competitiveness. A number of impressive and extremely challenging ascents were undertaken during these years, carried out by a group of exceptionally skilled climbers including Gianbattista Vinatzer from Val Gardena, Luigi Micheluzzi from Val di Fassa, Raffaele Carlesso, Alvise Andrich, and Riccardo Cassin. Some of these climbs represent the highest level ever reached in the Dolomites in terms of free climbing, up until the end of the 1960s. The “heroic” era of classic mountaineering (characterized by an essentially “free” climb that did not categorically exclude the limited use of artificial aids) ended with the onset of the Second World War.

A new era of alpine climbing began following World War II, accompanied significantly by new technical equipment such as the Vibram shoe sole and the evolution in the piton (produced in various shapes and sizes). Ascents in the Dolomites became characterized by increasing use of artificial techniques that reached disproportionate levels in the so-called “direttissimas” (bullet routes or more direct ascents) with “more pitons than climbing meters”. This was also an era of repeated ascensions – solo and winter – of the great routes mapped out in the 1930s. It was also a time when mountaineering received the most attention from the media who were often more interested in the loss of life and controversial issues than exposés promoting climbing.

After a somewhat-stale and conservative period in mountaineering that was also limited by the narrow-mindedness of alpine clubs, free climbing and clean climbing brought about an encouraging renaissance. These climbing styles abandoned aid climbing and traditional mountaineering tactics, as well as the idea that exhaustion, fear, and cold were synonymous with reaching the top. The sport of rock climbing quickly evolved into a distinct athletic activity and gradually began to have less in common with true alpine mountaineering.

”Up until July 1968, it was widely acknowledged that it was impossible to go beyond a Grade VI. Then something happened to change that...”

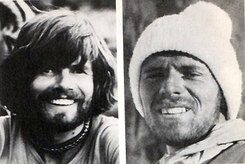

During the 1960s, there were still those who continued to practice traditional mountaineering but who adopted later advances in ethics and training: the alpine mountaineering practiced by Reinhold Messner from the South Tyrol and his younger brother Günther Messner was, in fact, the style used by the great climbers of the 1930s. In 1968, barely into their twenties, they executed their first ascent of the Central Pillar of the Piz dl Ciaval on the western wall of Sas dla Crusc, overcoming climbing difficulties that nobody had ever surpassed. In the following years, the Messner brothers succeeded in climbing some of the Dolomites’ most challenging routes – in terms of the level of difficulty and speed of ascent – as well as opening new routes in solo climbs and repeat winter ascents.

”The ascent of Sas dla Crusc by the Messner brothers – among the few ascents achieved on the peak – made it clear that mountaineering would survive only if it got rid of what was useless. Alpinism itself is useless, therefore only the absurd would keep it alive. The route on the Sas dla Crusc is precisely an absurd route. This is why it is aesthetically terrifying and poses disarming difficulties even today.” M. Cominetti.

Since then, technological advances concerning athletic training and physical and psychological preparedness, in particular, have removed the fears of the past for climbers who, aware of their skills tested at the valley floor, attempt the higher altitudes. In a short amount of time, the myths of yore have literally been demolished; the routes that were extremely difficult to traverse in one or two days and were once the prerogative of the chosen few are today classic ascents for thousands of travelers. The technical level of the great alpine mountaineers is now aimed at continuously trying to surpass previous records, in terms of difficulty and speed.

There are places all around the globe that provide the climate and geomorphologic characteristics for practicing specific sports and the Dolomites offer no less. In fact, they offer endless choices both in winter and in summer.

During winter months – from the beginning of December to early April – skiing fun is guaranteed. In fact, there are 63 ski lifts between Alta Badia and Plan de Corones, garnering Val Badia a place in the world-famous Dolomiti Superski skiing area. This circuit was created in 1973 thanks to the keen insight of a few businessmen in Cortina d’Ampezzo, Val Badia, and Val Gardena.

The Alta Badia ski resort has over 500 km of ski slopes with skis-on connection between slopes and direct connection to the renowned Sellaronda circuit. The Plan de Corones ski area, which includes San Vigilio di Marebbe, offers 116 km of slopes from the heights of Plan de Corones at 2, 275 m.a.s.l. bring you down to San Vigilio, Riscone, Brunico, Perca, and Valdaora.

For those of you who don’t care for slopes and ski lifts and prefer to enjoy the peacefulness of nature – no problem! Winter recreationists can enjoy many of the busy summer hiking trails in winter with snowshoes. Just another way to admire the winter wonderland of the Dolomite mountains…

Ski touring is another option for skilled skiers looking for the hidden rewards of nature. This sport is becoming more popular among amateur skiers because ski tourers can access mountain peaks and summits with breathtaking downhill runs, immersed in the exceptional beauty of the Alpine backcountry.

The area also offers ice climbing for the boldest adventurers who are looking for the excitement of ascending icefalls, frozen waterfalls, cliffs, and rock slabs covered with ice, abetted by crampons and ice axes.

In spring, as soon as the first snow starts to melt and temperatures begin to rise, cyclists come out of their long winter “hibernation” and begin training. During this time of the year, mountain roads are scarcely trafficked and a bicycle is the best way to enjoy the amazing scenery. The climbs of the famous Giro d’Italia through the Dolomites passes is an event that two-wheel (motor-less, of course!) enthusiasts cannot miss.

A wide range of sporting and recreational activities can be practiced starting in early June, when the last patches of snowmelt from the high mountain trails, until late fall. Roads and trails offer spectacular Mountain Bike excursions and the Dolomites High Routes are great hiking and running opportunities for those on foot. Trekking and in particular trail running along the High Routes is becoming increasingly popular among walkers and runners.

The Dolomites is an ideal starting point for those of you who love rock climbing and the via ferratas (fixed rope routes). While expert mountaineers can enjoy thrilling ascents up the challenging Dolomite rock walls reached by famous climbers, less skilled climbers can still reach unique and fascinating summits using ropes and anchors that facilitate the way up the rocky inclines.

Interestingly, most of the via ferratas in the Dolomites date back to the First World War when Italian and Austrian soldiers on the frontline in the Dolomites were forced to use fixed ropes, steps, and ladders to aid movement in the mountains. These equipped climbing routes were restored – especially in the 1960s and ‘70s – to make some of the most spectacular and celebrated summits in the Dolomites safely accessible to an ever-growing number of enthusiasts.

If you’re itching to try new “sporting thrills”, contact us for an offer made just for you!

Click here to go to the next page 'Nature'